or: How I learned to stop worrying and love the missteps.

Right now, I’m writing this as an unemployed 28-year-old from my parents’ house. The job market is dismal, I’m completely burned out from an intense year of grad school, and the election has wreaked havoc among my immediate family. And yet, I’m overall okay. I’m in a definite low point of my depression wave cycle, but I know the low will end someday. It’s been a long journey to equilibrium, and UX turned out to be a valuable resource along the way.

According to MayoClinic:

Depression is a mood disorder that causes a persistent feeling of sadness and loss of interest. Also called major depressive disorder or clinical depression, it affects how you feel, think and behave and can lead to a variety of emotional and physical problems…

During [depressive] episodes, symptoms occur most of the day, nearly every day and may include:

• Feelings of sadness, tearfulness, emptiness or hopelessness

• Angry outbursts, irritability or frustration, even over small matters

• Feelings of worthlessness or guilt, fixating on past failures or self-blame

• (etc.)

My story with depression is not new. Growing up as the sensitive, artistic eldest daughter of an immigrant family, I internalized every responsibility and negative thought around me. In the face of countless high expectations, I turned everything inward because I felt like I was selfish and unimportant, and taking on the burdens of others would somehow redeem my very existence. This has turned me into a neurotic ball of self-hatred terrified of forming relationships with others.

It was during a dismal time post-college that I came across UX through reading The Design of Everyday Things, which contributed greatly to a change in my outlook on life. According to the Nielsen Norman Group:

“User experience encompasses all aspects of the end-user’s interaction with the company, its services, and its products…True user experience goes far beyond giving customers what they say they want, or providing checklist features.”

I didn’t realize that I didn’t have to always blame myself for using something wrong. Other people stumbled over the same things as I did? And an entire field existed to make me (and them!) feel not as dumb? This broke my little brain.

Since then, I’ve leaped head-first into the world of UX. I’ve worked professionally as a UX Designer, then a UX Researcher, and gone back to school to earn my Master’s in Human-Computer Interaction + Design at the University of Washington.

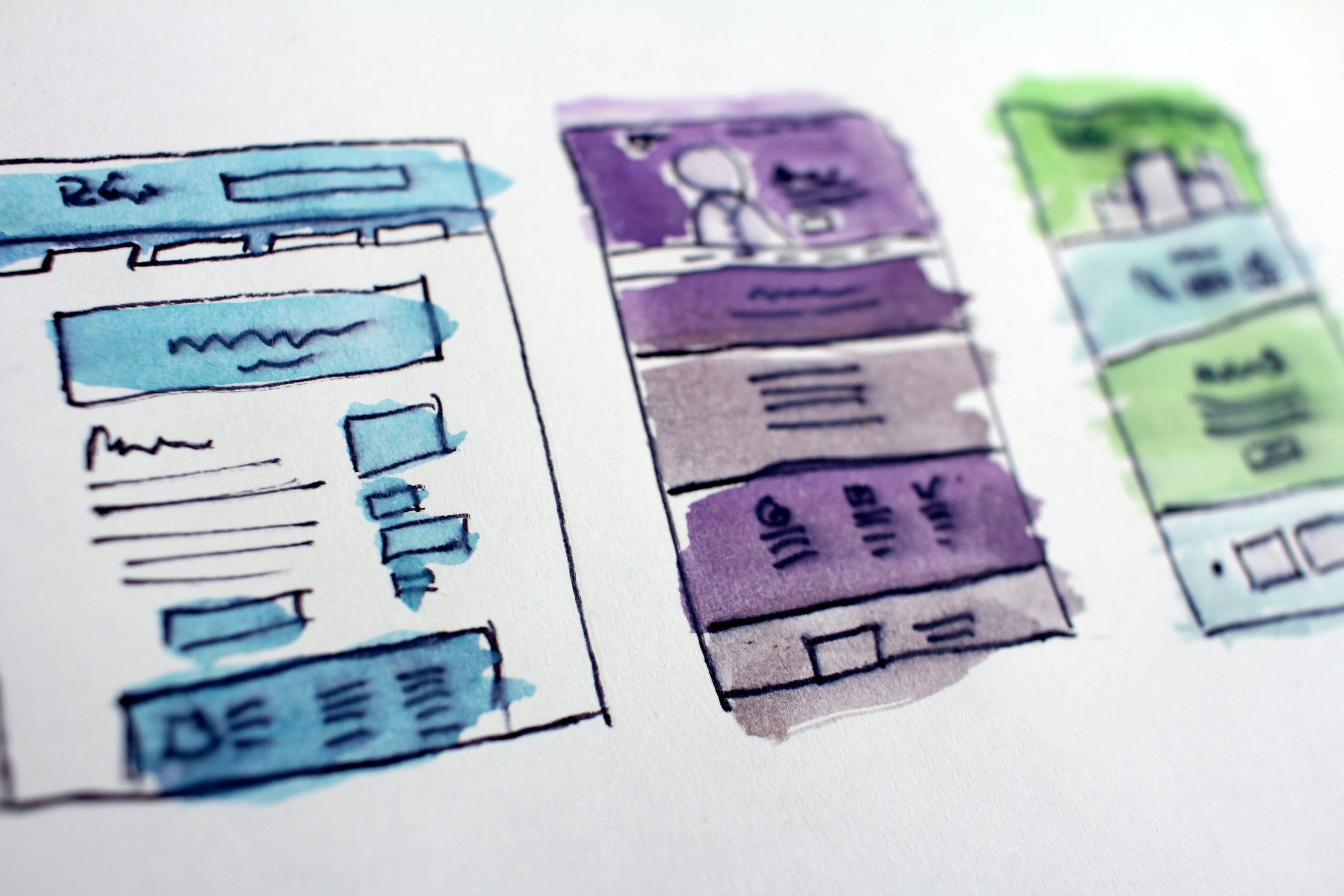

I’ve internalized UX into every part of my daily life. I am constantly on the lookout for good & bad user experiences, adding to my mental models, and asking probing questions about ‘why this?’ or ‘how that?’. By focusing on practical evidence & actions, I can consciously pull myself into an impersonal observer’s seat in order to fend off illogical fears that crop up.

Disclaimer: UX helped me a lot, but it worked alongside my faith, friends/family, and therapist. If you have the means, I highly recommend therapy!

Here are 3 lies that my depression has told me, and how UX (through excerpts from Don Norman’s book) equipped me to fight them:

1. I shouldn’t be making any mistakes.

“The idea that a person is at fault when something goes wrong is deeply entrenched in society. That’s why we blame others and even ourselves… But… human error usually is a result of poor design… Humans err continually; it is an intrinsic part of our nature… Pinning the blame on the person maybe a comfortable way to proceed, but why was the system ever designed so that a single act by a single person could cause calamity?”

UX says that the onus of a user mistake should not be on the user but on the experience of the product or service. If I screw up, it’s pretty useless for me to put everything on myself. Beating myself up doesn’t lead to anything good, be it my own mental state or future users’ experiences. Instead, I should diagnose what exactly went wrong as well as what actionable improvements might allow me and others to avoid it in the future.

Furthermore, the presence of user failure is actually an important warning sign of a deeper problem. A true worst-case scenario happens when a deep problem goes unnoticed for a long time, only to blow up with catastrophic consequences in the future. Uncovering these problems via testing is a critical part of building a solution.

For me, that means constantly exploring my own limits and accepting that I am and always will be a naturally failure-prone human being. I won’t be able to progress if I can’t accept myself at my starting point.

2. The consequences of making a mistake are unforgivable.

Even after I logically understand why mistakes are natural and I should not blame myself for making them, I can’t help thinking that bad things keep happening because I’m always screwing up. Existing societal pressures to ‘do better’ and ‘not mess up’ are always at play, and my depression monster uses these punish me.

Nobody ever plans to fail. Everybody wants to succeed when performing an action because there is no reward for messing up. When failure does occur, we recognize that this is Not A Good Thing™ for us and immediately switch to damage control mode. This shows up as excuses, defensiveness, and finger-pointing. In our mortification, how do we stop making failure all about us and instead learn to expand our vision to see what other factors were at play?

“[How can we overcome the] power of social pressures on behavior [which causes] otherwise sensible people to do things they know are wrong and possibly dangerous[?]… Good design alone is not sufficient. We need different training… to adequately address social, economic, and cultural pressures [which is] the hardest parts of ensuring safe… behavior.”

Truly world-breaking accidents don’t just happen because of one single incident. These things happen because the dominos were already (unfortunately) set up in such a way as to fall to disastrous effect. We can’t pin the blame entirely on the shoulders of that one unlucky person who knocked down that first domino. Instead, we should look toward the subsequent pieces to determine why they ended up in such vulnerable positions.

As for me, at the end of the day, I’m just one person with a limited range of influence. I need to stop pitting myself against such an unrealistic standard because that pressure feeds the vicious circle of social pressure -> failure.

3. I’m the only one making these mistakes, and everyone is so much better than me.

This is clearly a crock of bullshit. After running enough user tests, I learned to drop all my expectations in human success. With little exception, people fail to listen to instructions, have all sorts of differing expectations, and easily get frustrated. After seeing my users fail in increasingly creative ways, I resigned myself to stop idolizing people.

An unfair logic that my depression exploits is “if this person doesn’t mention making a mistake, that must mean that they don’t ever make mistakes”. So when it comes to reporting important errors, if nobody talks about it, it must not exist. There is a real stigma (both internal and external) associated with admitting to mistakes, and if you call attention to an error you might be blamed for it and suffer the consequences. Most systems in place protect the status quo and penalize those who criticize them. This is very human and understandable, but ultimately harmful.

The only way to reduce the incidence of errors is to admit their existence, to gather together information about them, and thereby to be able to make the appropriate changes to reduce their occurrence… Rather than stigmatize those who admit to error, we should thank [them] and encourage the reporting. We need to make it easier to report errors, for the goal is not to punish but to determine how it occurred and change things so that it will not happen again.

Instead of attempting change, it’s much easier to avoid cognitive dissonance by denying the existence of a broken system and labeling it as ‘something that just happens’ (in my case, “I’m just a lost cause as a person, and that everyone else somehow has a secret sauce that I lack”). This applies to every system imaginable, from government to relationships to simple everyday actions.

After identifying something in need of improvement, unfortunately, we still have to actually put the effort into improving it. No matter the context, motivation is intensely personal and illogical. Alas, I still haven’t found a surefire way to bamboozle my brain into tapping into this and I may never find one. At least I now know that I’m not alone in the struggle bus.

It’s way too easy to pressure ourselves into situations with no room for error, and then beat ourselves up when it happens. True, our stupid user judgement may be the final tipping point to a lot of domino-effect mistakes. However, fundamentally we are simply not set up for success, and neither do we set ourselves up for success. The fact that UX as a field exists is a testament to that truth.

A lot of this might sound a lot like petty schadenfreude, but seeing other people screw up and having to deal with the consequences has honestly cheered me up immensely. Think of it like watching an America’s Funniest Home Videos compilation — there’s just no way you’re coming out feeling at least a little bit happier after watching people wipe out (harmlessly). Depression isn’t a disease with a logical way to approach it. If petty schadenfreude and UX studies get through to my brain, I will take that as a win.

I’m still fighting an uphill battle to improve myself every day. I’ll observe a peculiar behavior of mine and root-cause-analysis it and disappointingly find that the root is old self-hatred caused by depression yet again. My stomach always drops a little upon realizing this (“I thought I was over this already”). But regardless of what I find, I’ve firmly decided that it’s time for me to stop listening to my depression monster and break out of that self-victim bubble.

If you are struggling with your own mental illness, I hope that reading this inspires you to keep on fighting. A lot of this comes down to your own tank of energy/willpower, so please take care of yourself during this (likely) more lonely holiday season and don’t be afraid to lean on any available resources when needed.

Here is a list of mental health resources from the University of Michigan.

If you are having suicidal thoughts and need immediate assistance, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1–800–273–8255 or chat online here.