Raymond Loewy and the birth of the design discipline

Like many UX designers, I didn’t aspire to be a UX designer when I was young. And like some of you converted UX designers, I did want to design products when I grew up. Physical products, appliances, shiny, rounded edges, ergonomic buttons, clever interfaces. At the time I didn’t know that this discipline was known as industrial design. I would later discover that industrial design was not my forte (neither was mechanical engineering or physics), but I still held on to a love for industrial designers, brilliant products, and famous case studies where engineering and design intersect perfectly.

Before there was a digital world that needed designing, all design existed as an analog discipline. Much of the foundational design thinking knowledge that created this generation’s most renowned digital experience designers comes from the early experiments in design for the physical world. Most of the concepts are the same — how can we not merely solve a problem, but to provide an enriching experience along with the solution? The use cases are often different, but ultimately, a shiny streamlined car and a smooth intuitive website are both pleasant packages to encapsulate an underlying motive.

If you had asked me last year when industrial design first began, I would’ve said approximately the Stone Age. If something can be made well, then something can be made better, and we know that rudimentary stone tools evolved over time to improve their functions, ergonomics, convenience, and durability. For what it’s worth, I still stand by this assertion. But it wasn’t until I read the book The Evolution of Useful Things by Henry Petrosky earlier this year that I learned of one very specific catalyst for the modern industrial design we know: Raymond Loewy.

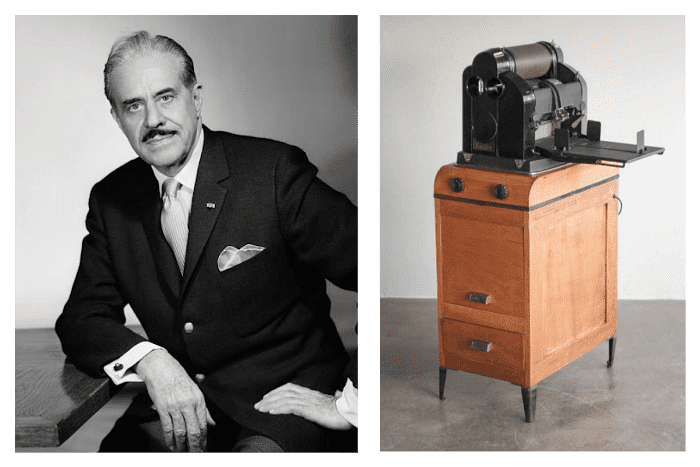

The Pioneer of Industrial Design

Raymond Loewy was born in Paris in 1893 before moving to New York City and establishing himself as a fashion illustrator for Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue. Along his trajectory as the first — and arguably most prolific — industrial designer, he would go on to design locomotives, packaging for Lucky Strike and Coca-Cola, the Studebaker Starline Coupe, the Greyhound Bus, the modern Shell logo, Frigidaire appliances, and so many others.

Among the concepts that Loewy pioneered was that of streamlining, which he described as “beauty through function and simplification.” The most iconic pieces of mid-century industrial design — teardrop shapes, smooth edges, and rounded corners — can all be traced back to Loewy.

The First Product

By the late 1920s, Loewy was growing restless in his role as a freelance illustrator. While working for Saks, he was given an opportunity to meet with Horace Saks to visit a newly opening branch store. He suggested that a department store like Saks should be treated like an integrated system, with internal consistency around the store, uniform appearance and demeanor among employees, and signature attractive packaging for purchased goods. These ideas took off and spread to become what we’re now familiar with at most department stores. And with that success, Loewy was ready for bigger and better things.

His big break came in 1929 when the company Gestetner approached him to redesign their duplicator machine, also known as a mimeograph. When David Gestetner first released his Cyclostyle duplicator machine in 1922, he boasted its ability to make 10,000 copies from a single Durotype stencil, which was a major achievement of its day. But for as impressive as the technology was, the device required many moving parts, gears, and exposed surfaces. By 1929, Gestetner decided that the next generation of his machine should receive an overhauled appearance and he enlisted the fashion illustrator Loewy for help.

For the 1929 release of the second generation duplicator machine, the original mimeograph would be mounted on top of a tabletop surface with a metal-framed set of drawers beneath that contained more gears and mechanics. Over the course of three days, Loewy produced a case that enclosed all of the internal moving parts that didn’t need to be operated or seen by the machine’s operators. Around the metal frame of drawers he added sleek wood paneling. Around the side profiles of the mechanical duplicator he added a single piece of flat, rounded metal that matched the contours of the mechanics. At every opportunity, Loewy employed rounded corners to create a continuous smooth flow from the device’s top to bottom.

As you can imagine, this simple solution made the second edition of the Gestetner duplicating machine much easier to sell and before long, most companies demanded designers like Loewy to come in and improve their struggling appliances during the Great Depression.

While this first design exercise is a long way from where design has come over the last century, the concepts remain surprisingly relevant today. Consumers demand increasingly complex technology — technology that requires unglamorous backend processing, deeply logical algorithms, and communication protocols that are meaningless to the end user. Everything we consider good product design today, from iconography to information architecture to animated loading screens, is an example of softening these edges and hiding the ugly mechanical parts.

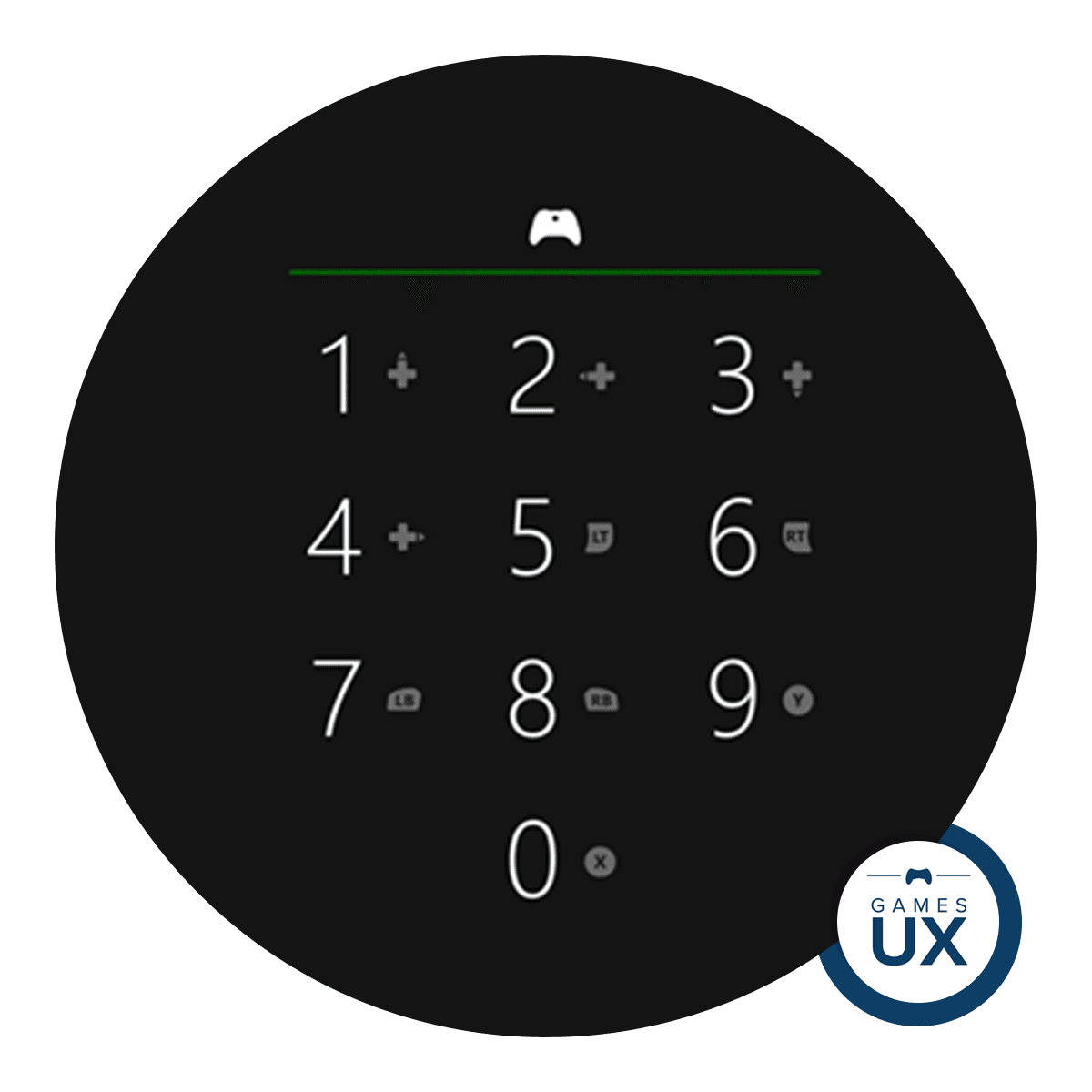

MAYA

Despite pioneering the field of industrial design and often the only designer in the room, Loewy understood the intricate tension among product requirements, engineering feasibility, and adoption by new users. He knew that designers held the potential to push boundaries of aesthetics, innovation, and futurism, but that customers have a limited tolerance to the speed of these changes. Loewy referred to this concept as MAYA: Most Advanced Yet Acceptable.

The adult public’s taste is not necessarily ready to accept the logical solutions to their requirements if the solution implies too vast a departure from what they have been conditioned into accepting as the norm.

–

Loewy

The idea of MAYA seems to be lost in the modern design world. So much more often we are concerned about producing a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) rather than the most advanced. The MVP addresses the tension we face where we have product requirements but our design aspirations are limited by time, budget, and engineering constraints. MAYA addresses the tension we face when we remove those constraints and instead crash into the psychological limits of users. We would do well to hold on to both of these concepts with equal weight, placing MVP and MAYA as the minimum and maximum ends of our design spectra and aiming for that maximum as often as possible.

Conclusion

Some of the more seasoned designers among us might have already been familiar with Raymond Loewy, but I was surprised to find that I didn’t recognize his name when it came up earlier this year. If his legacy is indeed slowly being lost to the Jony Ives and Julie Zhuos of the modern world, I hope this piece can help remind the rest of us of the humble beginnings of our industry. Among the professions of the world, product design is relatively young, and UX design is even more nascent. Both disciplines have advanced quickly in that short time and we’re lucky to have so much documentation of their histories.

One final thought: Raymond Loewy would be 128 this year. Would he be proud of the direction design has taken since his death in 1986? Would he be impressed by the significant investment companies make in their design practices today? Would he think that our best products are the most advanced yet acceptable? Feel free to weigh in in the comments.