Build Design Systems With Penpot Components

Penpot's new component system for building scalable design systems, emphasizing designer-developer collaboration.

medium bookmark / Raindrop.io |

Patton Oswalt once did a bit about how much we take for granted the fact that we all live in the future. We walk around obliviously with devices in our pockets—smartphones about the size of an ’80s mixtape—that contain every song we’ve ever heard, or will ever hear. Which makes, to a certain sort of person, the renaissance of vinyl so inexplicable. When you can already stream all the music ever for the cost of a $9.99 Spotify subscription, why would anyone spend $30 on a single record impressed in wax?

Of course, the fact that most of us have such ephemeral relationships with music these days is why vinyl has come back. Embracing vinyl in the 21st century isn’t just about being hip; it’s about reclaiming a physical relationship with our music, one that has largely been lost in today’s streaming age. For vinyl collectors, buying an album elevates it, marks its importance. Moreover, vinyl’s physicality invites us to have a more active relationship with our music. It’s not something that can be engaged with passively: You can’t listen to it while you jog, or ride the subway. To play a record, you must set out to listen to it, not just hear it—take it out of its sleeve, drop the needle, sit down in front of your stereo, and flip it halfway through.

Which makes vinyl more important than just an obsolete medium. To those who collect them, vinyl records are artefacts, physical mementos of our most profound musical relationships. That’s why, more and more, we vinyl collectors expect records to be as unique as the music they contain. Luckily, vinyl designers have been up to the task, showing extraordinary ingenuity when it comes to making records as distinctive as the waveforms they contain. Here’s a quick primer on the genres of the world of designer vinyl.

A record isn’t much more than a circular waveform that gets traced by a needle, which means that any solid material can technically be a record. Before vinyl, for example, Thomas Edison used tin foil, as well as wax paper, to make his crudest early recordings. Wax cylinders, glass, and shellac followed, until PVC finally became the go-to material for record manufacturing.

But designers keep experimenting. The famous Golden Records sent out into space aboard the Voyager Spacecraft in 1977, for example, are made of gold-plated copper and electroplated with uranium-238, so that alien civilizations can use its 4.468-billion-year nuclear half-life to determine the record’s age.

More recently, the Swedish band Shout Out Louds created a record out of ice. Ten fans were sent an ice mold, which—when filled with water and frozen—created a playable ice disk of the group’s single “Blue Ice.” Similarly, French DJ Breakbot had 120 copies of his single “By Your Side” pressed in edible chocolate. And then there are 3-D printed records, and even records made of laser-cut wood.

My favorite improbable record material, though? Soviet-era X-Ray records, nicknamed “Bone Music.” Because vinyl was scarce in the U.S.S.R., Soviet bootleggers pressed these unusual records on old X-Ray film, which was plentiful and cheap. Once the X-Ray was pressed, replete with an irradiated skeletal design, the record was cut into a crude circle with manicure scissors, and then burned through with a cigarette hole, so it could play on a standard stereo deck.

Maybe the easiest way to make a record stand out is by mixing the vinyl with something else, like a dye to make the record more colorful. But some manufacturers have taken this idea far beyond a little color shift.

For National Record Store Day in 2012, the Australian-American rock band Liars released Mess on a Mission, an album with tangles of multicolored yarn pressed inside. Another special Record Store Day 2012 release was Jack White’s Sixteen Saltines, a lava lamp of a record with translucent blue liquid literally pulsing between the sheets of vinyl. And dried rose petals were pressed into the seven-inch clear vinyl release of Karen Elson’s Vicious for 2011’s Record Store Day.

Then there are the unmentionables. Hellmouth, a hardcore Detroit metal band, burned an old German Bible from the 1800s and pressed it inside Gravestone Skylines. Likewise, Barren Harvest filled a clear vinyl limited edition of Subtle Cruelties with fallen autumn leaves that each impart their own subtle acoustic signature to the record when played. And the less explicitly said about what Eohippus’ 2014 release of Getting Your Hair Wet with Pee is filled with, the better, except to say it’s all in the title.

Waxworks Records’ “Friday the 13th”

The most gruesome kind of vinyl literally bleeds when you cut it, though. Many artists have filled records with blood, from the delicate whorlings of Perfect Pussy’s Say Yes to Love to the hemoglobin sandwich of the Flaming Lips’ Heady Fwends. My two favorite examples of this genre, though, are soundtracks to horror movies: the 2014 limited-edition release of Waxworks Records’ Friday the 13th is filled with a few cc’s of the red stuff, while Mondo’s 2016 release of the Aliens OST is filled with green Xenomorph blood — fake, of course, since the real stuff would melt right through.

There’s no reason a turntable needle can’t trace a groove in any shaped vinyl you want—rectangular, triangular, or octahedral, for example—but there’s a reason records are mostly circular: It’s efficient. All it takes is a belt and a motor to make a wheel turn, which is why most records are circular.

But not all! In 2013, the soundtrack for Batman: The Animated Series was released in—what else ?— the shape of the bat symbol. In 1986, Talk Talk’s “Living in Another World” — a single from their album The Colour of Spring — was cut in the shape of a butterfly with tiger eyes, which is about the ’80s-est thing I can think of. And for Maybe I’m Dead, Money Mark — a longtime collaborator of the Beastie Boys — released a ten-inch shaped like a chihuahua.

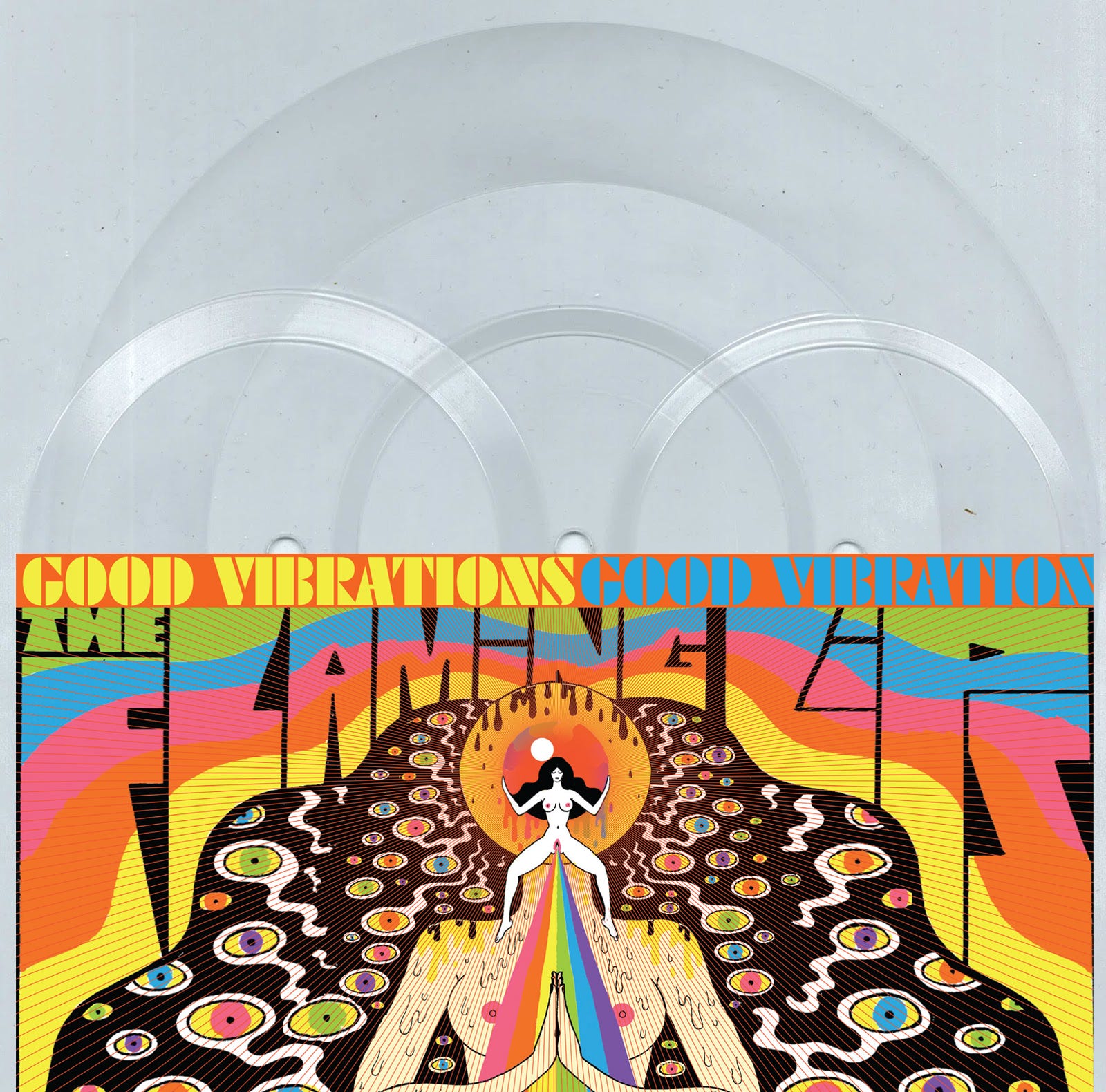

The Flaming Lips’ “Good Vibrations”

The most interesting record shapes, though, aren’t pressed with traditional vinyl-cutting machines. They’re cut with lathes, which makes some amazingly cool record designs possible. For example, the Flaming Lips’ 2015 release of Good Vibrations has four different “sides” (most records have two), and three holes (again, most records have one), but can only be flipped once. Or check out Son Lux’s four-“sided” record, which interlaps circles to fit essentially four different records on a single side.

This is my favorite genre of vinyl design.

The earliest mediums of animation depended on rotation. Consider zoetropes, which use a cylinder with vertical cuts on the side to create the illusion of motion for a succession of images printed on the other side. There’s also magic lanterns, an early type of projector that used configurations of hand-painted, rotating slides to animate things like the moon circling the earth, or mice jumping into a cat’s mouth. Kaleidoscopes are made by looking into a turning barrel filled with shards of colored plastic and glass. Even a spinning reel of film essentially animates individual frames by blurring them together in a circular motion.

Since all records spin, then, they have a built-in method of animation available to them. That’s a method vinyl designers have used to great effect.

Soundtrack for “Star Wars: The Force Awakens”

Records have been turned into the earlest animation devices. Zoetrope vinyl, like Sculpture’s seven-inch release of Plastic Infinite, comes to life under a simple strobing light. Laser-etched vinyl, meanwhile, uses the rotational blurring of a turntable itself to blend an abstract stationary design into a more visible emblem, like how Split Enz’s I Got You animates to show the Superman logo. And there’s no dork alive who wouldn’t chew off an arm to own a copy of the soundtrack to Star Wars: The Force Awakens, which animates a holographic TIE Fighter when illuminated with a mobile phone flashlight.

As for a vision of the future? Look no further than augmented reality. From Brian Eno, the rock pioneer behind the Windows 95 sounds, comes this app which turns spinning records into AR playgrounds, where metropolises of outside architecture erupt from the vinyl of a spinning record for the listener to explore.

Apps like this show that the technology and design of vinyl is far from obsolete. It’s just getting started.

Magenta is a publication of Huge.

AI-driven updates, curated by humans and hand-edited for the Prototypr community