Build Design Systems With Penpot Components

Penpot's new component system for building scalable design systems, emphasizing designer-developer collaboration.

medium bookmark / Raindrop.io |

“Tyler — art and design classes can be a lot of fun, but you really should be focusing on the subjects that will help you get into a good school and land a good job. They’re called ‘starving artists’ for a reason!”

I received these words in an email from a mentor in middle school after expressing my desire to take more art and design classes one semester. Like many of my teachers and mentors, he regularly stressed that studying science, technology, engineering, and mathematics was the best shot at a stable career — and I mostly agreed. I enjoyed these subjects and understood their practicality, but I didn’t see what the harm would be in taking a few introductory art and design classes to supplement Chemistry and Trigonometry.

As I was starting my Sophomore year of high school, the 2008 financial crisis hit. Hundreds of thousands of Americans were losing their jobs every month, including parents of close friends. The prospect of not being able to pay a mortgage or grocery bill suddenly became very real. I knew I needed to pursue a course of study that would lead to a secure career — hopefully one that I also would enjoy.

As graduation approached, my mentor’s words were at top of mind, and I began applying to universities across the country with well-ranked STEM departments. I ultimately decided to attend Princeton, where I began fulfilling Biology and Pre-Medicine course requirements.

With a practical degree in the works, my fear of a jobless future had slightly abated, and I began delving further into the subjects that, due to their perceived impracticality, I was never encouraged to explore.

My packed class schedule didn’t allow me the flexibility to enroll in many visual arts or design classes, but I managed to find creative outlets outside the classroom. One night during my Freshman year, I attended a recruitment event for Princeton’s Student Design Agency, a group that created posters, logos, and websites for campus-affiliated organizations. I filled out an application form, attached a few club flyers and posters I had designed in high school, and dropped it all in the agency’s mailbox.

I was rejected.

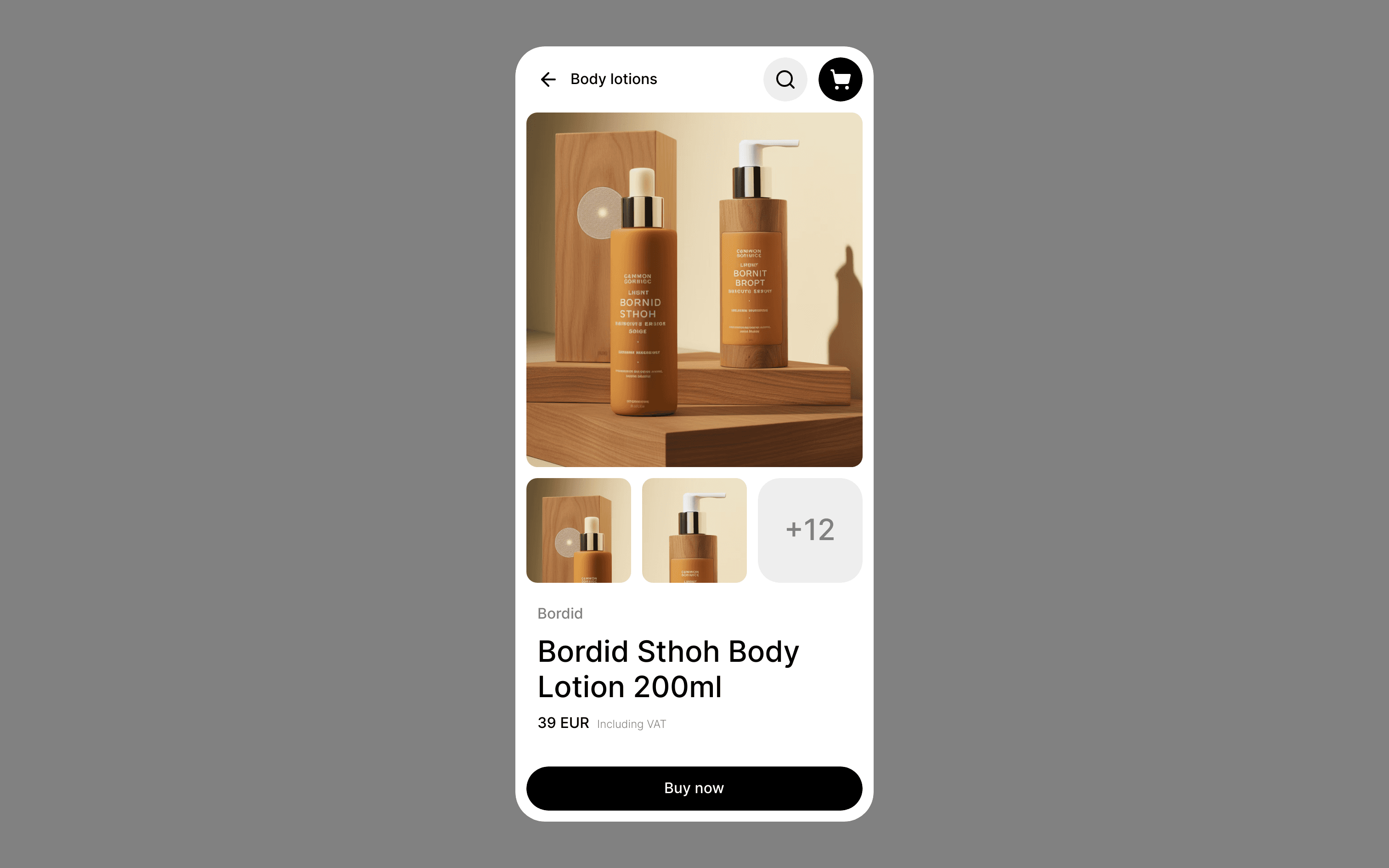

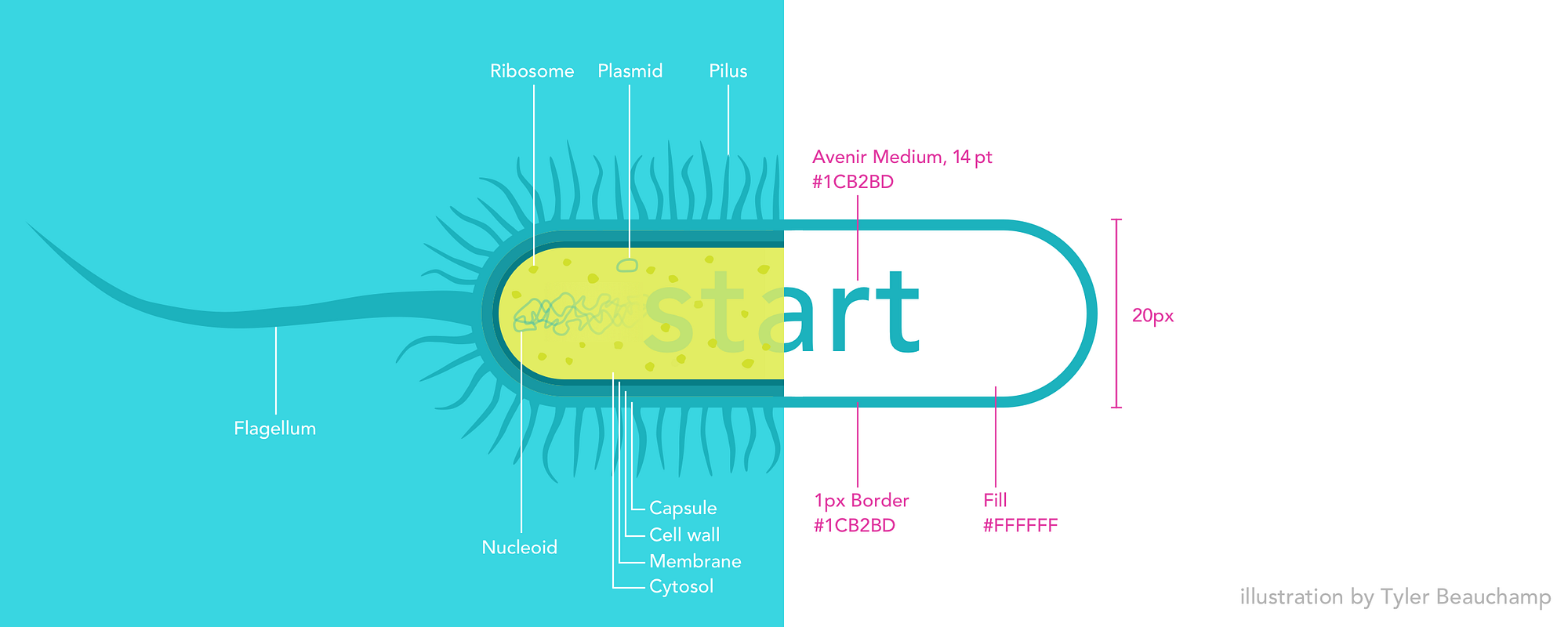

Looking back at these designs (which are too embarrassing to even include in this article), it’s clear that my rejection was more than justified. Fortunately, experienced members of the agency were still willing to teach me about basic design principles and how to use design tools like Adobe Illustrator. I applied again the next year and was accepted. During my time with the agency, I designed promotional materials for a wide variety of campus events, from Rubik’s Cube competitions to lectures about statistics.

Some of my first Student Design Agency poster projects

The bulk of the agency’s work was related to graphic design, but occasionally website and app design projects would crop up. I wanted desperately to be involved in these projects, but I didn’t have the user experience skills required at the time. So, I sought to learn as much as I could about UX principles, and then created fake projects to try out what I learned.

The example most ripe for a fake redesign project was the navigation system in my dad’s car (car UX is notoriously terrible). I sketched some redesign ideas with pencil and paper, and taught myself how to create workflow diagrams, wireframes, and high-fidelity prototypes using Sketch.

These kinds of fake redesign projects can make some designers cringe, and I understand why. It’s easy to add a fresh coat of paint to an ugly interface, and post the gleaming ‘finished product’ on Dribbble without doing any research or conducting a single usability study. Even so, these fake projects were a great way for me to learn how to use new design tools and practice designing interfaces — skills I couldn’t have developed by just reading about them.

While I was just starting to learn about the basics of user experience, several of my college friends were forming their own startups. One of these startups, Noteflo, had several talented software engineers on its team, but no designers. I was getting bored with my fake projects, so I jumped at the opportunity to help out.

Noteflo was a platform for students to share their class notes. By uploading notes, students earn points that could then be used to download other students’ notes. The Noteflo team asked me to design their logo and user interface.

I thought it was a really clever idea, and early user tests showed a lot of promise. Unfortunately, the Noteflo website was shut down by school administrators shortly after launching.

Notes are organized by class, type, and week. Each set of notes includes information about the note’s quality, format (handwritten or typed), and a first-page preview, so users know what they’re getting before they spend their points.

In the fall of 2013, I attended the Out For Undergrad Technology Conference at Facebook’s Headquarters in Menlo Park. Out For Undergrad is a non-profit organization dedicated to helping high-achieving LGBTQ undergraduates reach their full potential. Attending the conference was a wonderful experience; I made friends and networked with students from across the country, and learned about the career paths of successful tech leaders from companies like Facebook, Twitter, Apple, Amazon.

I loved the conference so much that I joined the Out For Undergrad team in 2014 as Design Director, and I’ve been working with them ever since. Today, I help with the branding, marketing, and growth of the organization. My work includes designing materials for its four yearly conferences, including signage, student binders, slide decks, and t-shirts. I’ve also moderated design discussion panels and led student mentorship groups at the technology and marketing conferences.

I’m very proud of the work I’ve done with Out For Undergrad. I’m so lucky to be able to work with an organization that has made an impact in thousands of students’ lives.

O4U logos and marketing materials

Out For Undergrad Tech Conference at Twitter’s San Francisco HQ

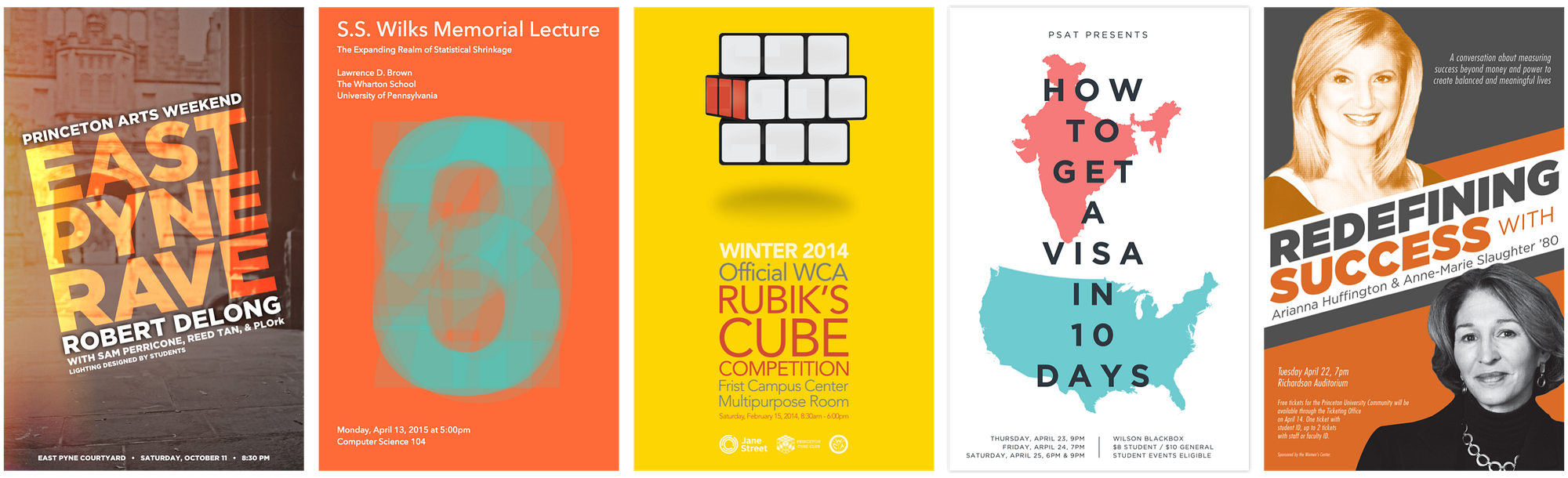

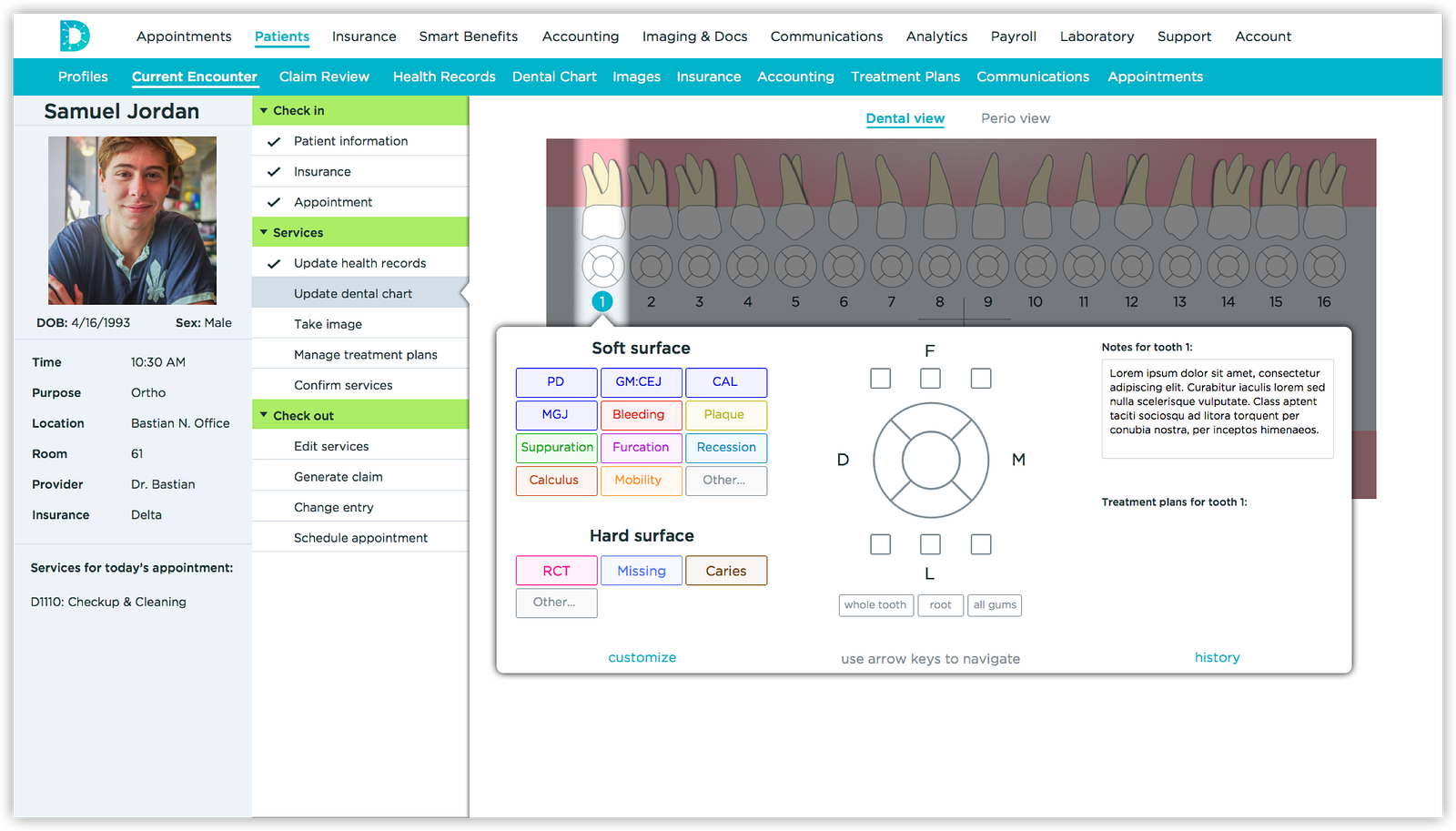

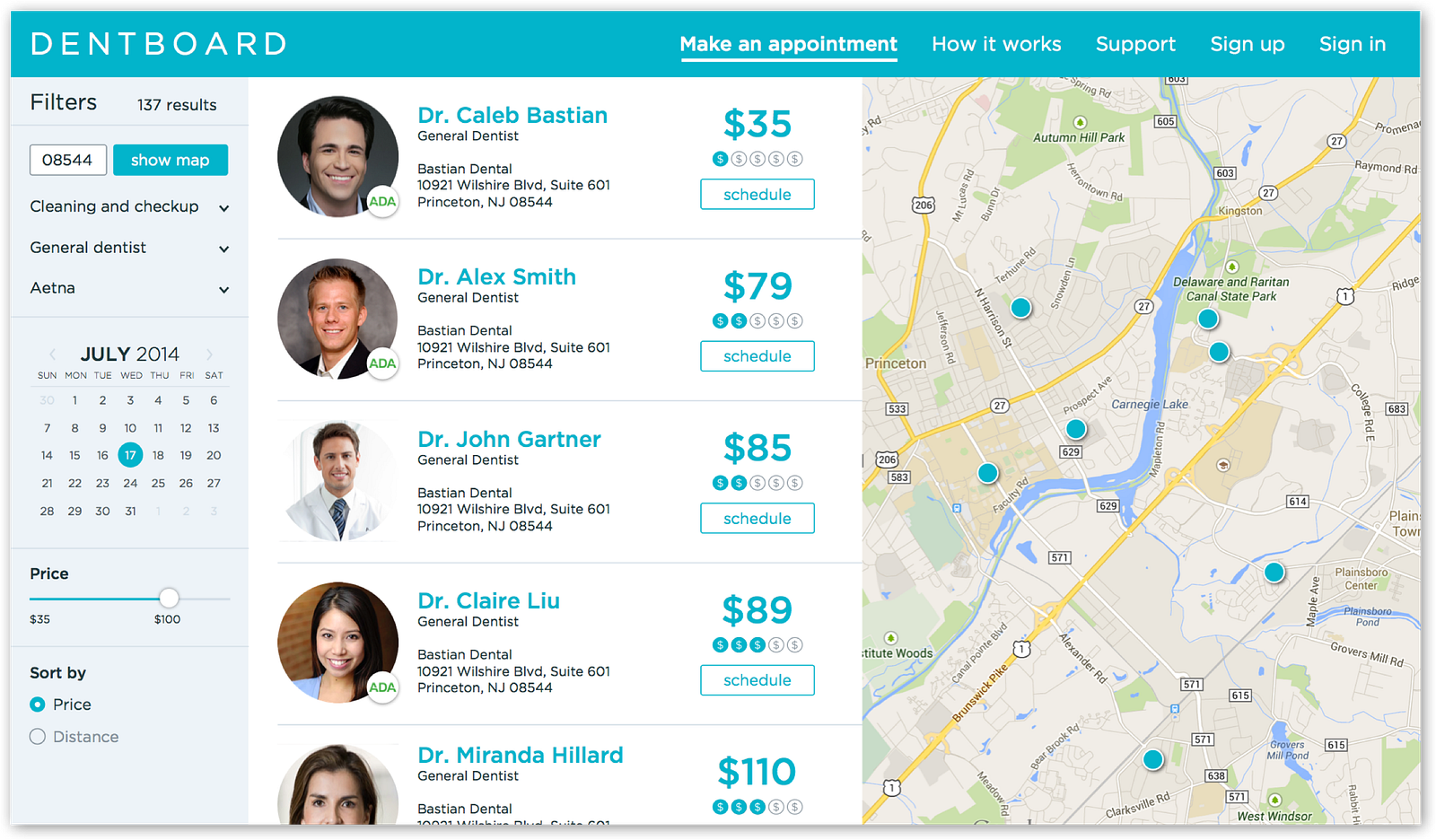

During the summer of 2014, I interned as a UX designer at a small startup called Dentboard. The goal of Dentboard was to bring efficiency, access, and profitability to dental offices with simple, cloud-based software.

I worked with a tight-knit group of 5 developers to build 12 practice management applications for dentist offices, as well as a consumer-facing website for patients to find dentists on the Dentboard network. I learned about the intricacies of periodontal care, the convoluted dental insurance market, and how to communicate with developers using HTML, CSS, and JavaScript terminology.

One of Dentboard’s professional applications showing a typical encounter workflow, which includes check-in, documentation, billing, and check-out.

Dentboard’s consumer website was designed to allow patients to filter dentists in their area based on appointment type, insurance, availability, and price. Patients could schedule appointments and pay bills online.

After I finished my internship at Dentboard, I knew I wanted to continue exploring UX design, but I had a lot of doubts about being able to get a design job without any formal design training or coursework. Nevertheless, I began to apply to product and UX design roles that fall, and secured interviews at Microsoft, Goldman Sachs, Dropbox, Wealthfront, Epic, and athenahealth.

During some of my on-site interviews, I talked with other applicants and realized that most of them had much better credentials and experience than I did. Even so, I felt confident that my past work would show interviewers that I had the potential to successfully learn, grow, and be an asset to their companies.

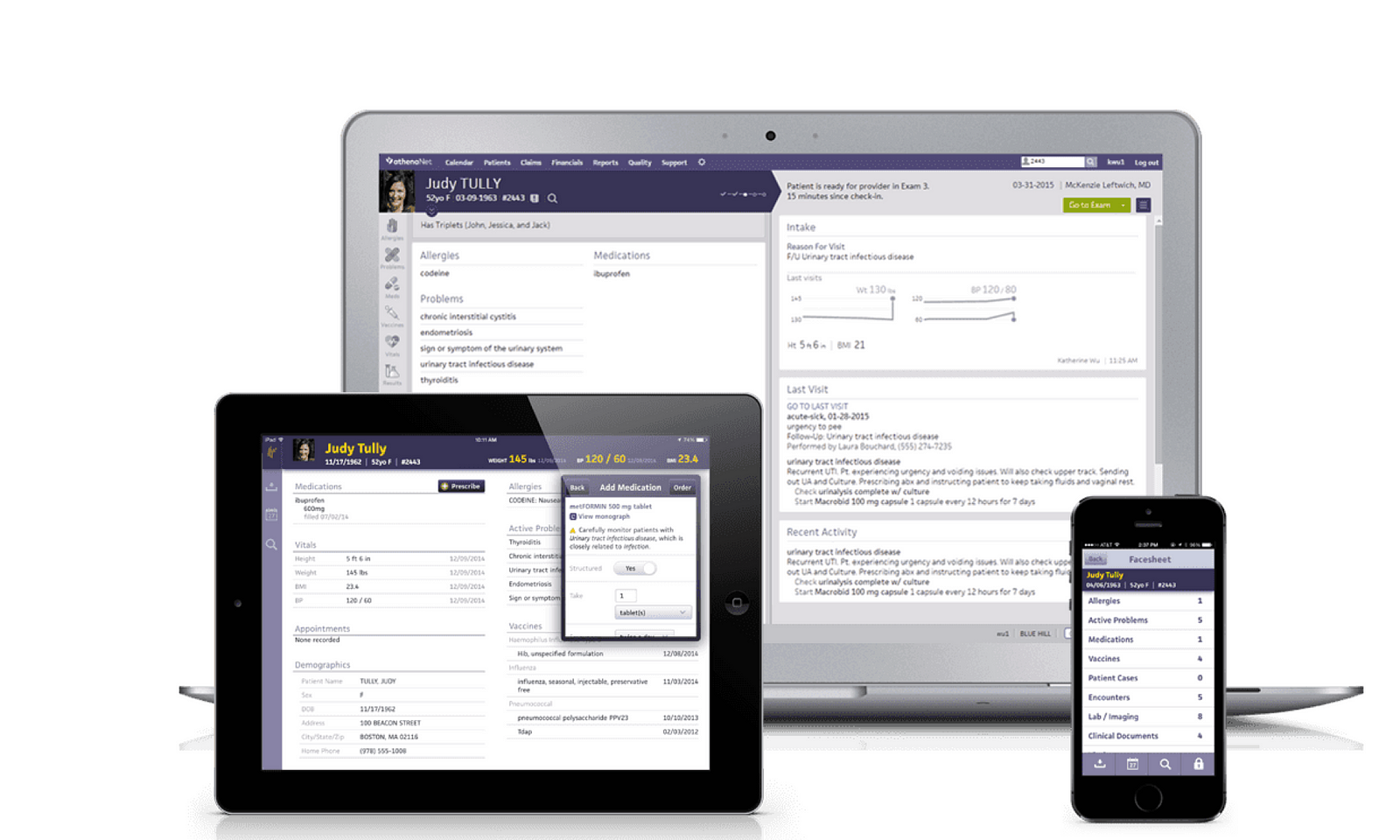

I accepted an offer at athenahealth at the end of 2014, and moved to Boston the following summer to join their Experience Design team. For the past few years, I’ve been working with product managers and developers to help doctors and nurses do what they do best: provide care to their patients.

The patient briefing page on athenaNet

I often travel to small critical access hospitals across the country to talk with the doctors and nurses who use our products. From their feedback, I create prototypes to test with these users, either on-site or remotely.

My design process usually starts with rough drawings, followed by static prototyping in Sketch, then interactive, high-fidelity prototyping in Principle, Framer, or InVision, depending on the nature of the project. For more details about my prototyping process, check out the article below.

As much as I love prototyping and visual design, they are not the most important parts of my job. It is the more scientific aspects of user experience —user research, testing, and interpretation of data — that inform me whether my designs are helping doctors and nurses to spend less time doing computer work they hate, and more time with the patients they care for.

Thanks for reading! If you’re interested in learning more about what I’m working on, feel free to reach out:

One clap, two clap, three clap, forty?

By clapping more or less, you can signal to us which stories really stand out.

Be the first to write a response…

prototypr.io

AI-driven updates, curated by humans and hand-edited for the Prototypr community