Build Design Systems With Penpot Components

Penpot's new component system for building scalable design systems, emphasizing designer-developer collaboration.

uxdesign.cc – User Experience Design — Medium | Fabricio Teixeira

Hello, old friend.

Hello, old friend.

We all reach a point in our careers when we start speaking in public. Designers, in particular, are pretty good at organizing conferences, panels, meetups, livestreams and other forms of publicly sharing knowledge with fellow designers.

Speaking at design events is not only important for the design community as a whole, but also for the people speaking. Here’s why:

Let’s look into a few things you can do to make sure you and your audience get the most out of those thirty minutes.

Before the presentation

Speaking at a conference can be a rare opportunity to show your design thinking and vision in public, so you need to be thoughtful about the topic you pick. Start with a list of ~20 different topic ideas, and then apply the following filters:

You have to be able to summarize your talk in one sentence. There’s always the temptation of trying to cover too many topics in a single presentation, or adding too much detail, or filling the presentation with too many examples.

Some people pick brainy topics with complicated words in it to sound like a real specialist, but that doesn’t really help the audience. Part of a designer’s role is to make interfaces simple, accessible, and easy to understand. Same thing applies to presentations.

In addition to that: you’re never going to be able to go in-depth in the topic you are covering in the 30 minutes you have. Bombarding people with too many concepts without properly explaining them is only going to make them scared or confused.

This is easy. 30 minutes? Less than 30 slides. You don’t want to have too many slides in your presentation and have to rush through them without giving people the time to digest what you are saying.

Let’s be honest: if a slide has more than two sentences in it, you won’t read it; you will wait for the presenter to verbally explain what is in there, ideally in a shorter or simpler way. Plus, the more content you put on your slide, the more you risk sounding too dense or too complicated.

When I see slides with too much content, or with bad design or hierarchy, all I can think about is how confusing that person’s wireframes must be. Or how messy their living room is.

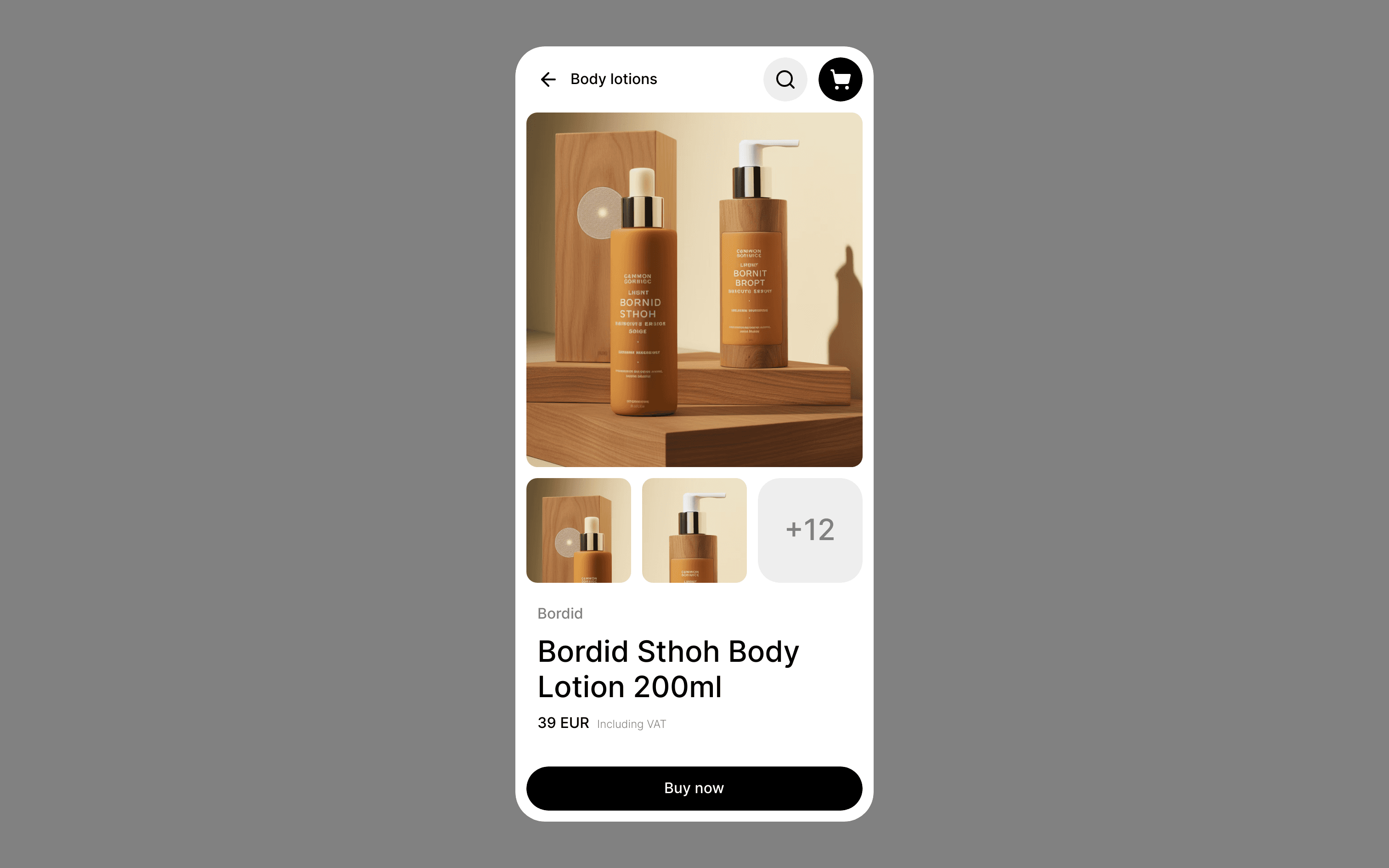

You are probably building your slides in a Macbook, and you probably love how crisp, colorful and beautiful your retina display is. Unfortunately, Apple still hasn’t entered the market of building 6-foot screens for incredibly illuminated environments. There is a big chance your slides are going to go through a terrible projector, and that all that light is going to bring your contrast down in about 30 or 40%.

Design your slides with that in mind.

Design your products with that in mind as well.

Each speaker has their own rules and best practices when it comes to practicing the presentation ahead of time. Some people don’t like to practice before hand; they would rather go on stage and talk about whatever their heart tells them to.

How good at improvisation are you? Let that dictate how many times you are going to go through your presentation in front of the mirror — if any.

During the presentation

Naturally, your first few talks can be frightening. It takes a lot of nerves to go on stage and speak to a big crowd — but that only gets better over time. Everyone who is now a great presenter, has gone through panic attacks, stage fright, dry mouth and shaky hands.

Best thing you can do is practice. Knowing the words that are going to get out of your mouth will save you mental bandwidth to focus on other aspects of your presentation (e.g. body language) and overall increase your level of confidence when you start talking.

But hey — why not just embracing the fear?

Fear is also part of the journey, it is what is going to make you stronger. Enjoy it. Embrace it. This is one of the greatest moments of your life and you want to skip through it?

The first one or two minutes of your presentation are key for the audience to decide between one of these:

Plan the first few slides accordingly.

Don’t present looking at the screen behind you. People are there to see you, not your slides; give them what they are looking for.

Here is a little secret that works for me every time: before even starting your talk, take a few seconds to look at the audience. Look around, in silence. Find faces. Smile. Look eye to eye; you don’t need to say anything. Yes, it is going to be a bit awkward. But this is going to make you finally accept the fact you are in front of a lot of people — and ultimately make you feel calmer during your presentation. Trying to mentally deny that people are staring at you will only make you feel unnatural as you start talking.

Here is something teachers tell you when you are a kid: “avoid walking too much on stage during presentations; that shows people you are nervous”. Well… unless you find ways to make all that movement feel like excitement. Rule number one in this case is: be yourself. Trying to concentrate in your body language and how much you are walking will distract you from getting your message across.

Like every story, it should have its ups and downs. When the rhythm of the story gets too even, you start to lose people’s attention. Plan a few peak moments every 5 or 6 slides to make sure you grab people’s attention back.

These “peaks” can be:

We’re all humans here. Stop trying to reach perfection. Show your flaws. If you are nervous, it’s fine to acknowledge that. People know public speaking can be tough. If you mispronounce something, make fun of it. If you have an accent (oh hey!), make a joke about it. When you show your human side, there’s a bigger chance people will relate to you and pay more attention.

After the presentation

There are two types of people who raise their hand to ask questions at the end of a presentation:

The reality is: you are not going to be able to solve all of the world’s problems when answering someone’s question in 30 seconds at the end of a long presentation. You won’t be able to understand the entirety of that person’s context to be able to really help (the size of their company, their team structure, the client they are dealing with, etc.). So the best thing you can do is to give a short, topline answer, acknowledge the complexity of the situation, and then offer to continue the conversation offline after the talk.

That’s why people go to these events in the first place.

When you walk out of stage, it’s natural that some people will try to find you to introduce themselves, ask a question, or simply thank you for your presentation. Be nice.

Good old Slideshare is still a pretty easy and powerful tool to share your presentation with the world. Upload your slides as soon as you can, so you don’t lose momentum of people Googling your presentation title to find out more about you and your slides.

A 30-minute presentation is not enough to cover almost any topic in depth. This is a good opportunity to write a follow-up piece that recaps what you covered in your presentation and adds a few more layers or perspectives to the story.

Best practices for public speaking in design conferences and events was originally published in uxdesign.cc on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

AI-driven updates, curated by humans and hand-edited for the Prototypr community