Build Design Systems With Penpot Components

Penpot's new component system for building scalable design systems, emphasizing designer-developer collaboration.

medium bookmark / Raindrop.io |

Have we lost the plot when we talk about delightful design? Here is my take on it. If some of it seems totally obvious, I agree. It should be.

My worry is that we currently care more about delightful elements of design than we do about delivering useful, helpful and empowering designs.

The Mailchimp High Five is a popular example of a delighter. Kudos to the team who came up with it. To fully appreciate it you need to have spent a lot of time crafting an email which goes out to thousands of people, then finally hit send and feel the relief of stress. But here it is.

https://dribbble.com/shots/1548634-MailChimp-High-Five

It’s extremely rewarding to see someone in a user-session have a positive experience and then smile, laugh or comment about that little je ne sais quoi, put in there to make a more human connection with them.

The reason why the mailchimp high five works as a delighter is because the underlying service does a great job of fulfilling user needs. It’s easy to use and it’s useful.

In order for your delighter to have a positive effect, you must first meet or exceed the user’s basic expectations. Otherwise that moment will likely add a layer of cheese on top of the original disappointment.

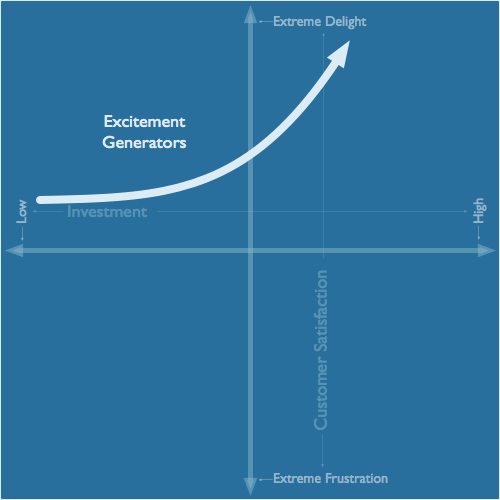

Understanding the Kano Model can help us understand how delight really works in design.

The Kano Model was created by Noriaka Kano in the 1980s to model how aspects of customer service have different effects depending on the customers expectations. It’s made up of 3 categories of ‘investment’.

– Basic expectations

– Performance payoffs

– Excitement generators

I’m going to lean heavily on Jared Spool’s description here as I think it’s explained very well. I’ve also used his graphs. Thanks Jared.

I’ll start with the definitions and then use my favourite spanner as an example.

https://articles.uie.com/kano_model/

Satisfaction of a product/service comes from meeting basic expectations. If you don’t meet these basic expectations, your product drops below satisfaction into frustration. You can go no higher than satisfaction until you first meet these basic expectations.

You can think of basic expectations as your design just doing the things the user knows it should be able to do.

Further investment in basic expectations beyond meeting satisfaction is a waste of effort. The user will not become any more satisfied.

Investment in performance provides a steady return on effort in terms of the user’s experience. You can think of this as designing features and processes which work better, do more, are quicker and are easier than they were previously.

Improving performance factors will see a steady increase in satisfaction which can eventually delight your users if you improve them enough.

It’s the user’s perception of performance we’re talking about here and not a number on a dashboard in your office. If it isn’t perceived as improved performance by the user, then it’s not improved performance in terms of the experience.

Excitement generators are the things which generate a more emotive reaction from the user and/or an attachment to the product. They can be lovely touches of thoughtfulness in the design, but also things like the language the product uses and the personality it has.

https://articles.uie.com/kano_model/

This is the space in which delighters live. Notice where this line starts. Investing effort in excitement generators is pointless until satisfaction is already moderately high.

Let me show you something I consider to be a delightfully designed object. It is my 15mm spanner I use for my singlespeed bike. Its main function is to allow me to get the wheels on and off. How can such a thing possibly be delightfully designed? I’ll explain.

There are examples within it of designing for basic expectation, performance and excitement generation. They might not have been consciously designed with that in mind. But they are there nonetheless.

It fits well on a 15mm bolt and is made of strong metal, so it keeps its shape despite repeated hard use. Investing further in the quality of the metal will have no impact on my level of satisfaction with it. But if the metal dis-formed, it would be game over in terms of my satisfaction. No increased performance or excitement could make up for the lack of this basic expectation.

It is small enough to fit in the pocket of a cycling jersey. Normally, because of reduced leverage, having a spanner of this size would make it very difficult for me to loosen a tight bolt without getting a sore hand. Equivalent spanners tend to be a lot longer and harder to carry.

But the spoon-shaped handle means I don’t get a sore hand and the spanner is designed to sit at an angle which prevents my hand flying into the wheel spokes when the tension is finally released and the bolt starts to give.

This investment in performance makes it a delightfully design object for me. But there’s more.

Singlespeeders are obsessed with craft beer, they often talk about beer more than bikes. This tool is designed for singlespeeders and so doubles up as a bottle opener which is not only really useful, but it also says “I know you”. It creates a connection which goes beyond its basic function.

If you know a singlespeeder, buy them one of these the next time you need to give them a present.

However if this tool was made of soft metal, it wouldn’t even meet my basic expectations. The great ergonomic design would seem an unfortunate missed opportunity. The bottle opener would be downright annoying.

It often angers people when a product doesn’t give appropriate focus to their basic needs and then provides added extras which they’d rather the company hadn’t spent any effort focusing on.

I’m going to use a rather old example, so I don’t need to poke at any specific current work to make this point. Even Microsoft accepts Clippy was a phenomenally poor piece of work on their part.

Image from Microsoft

Clippy was annoying mainly because he wouldn’t leave us alone to get on with what we were doing. He also thought he knew what we wanted when he often didn’t and tried to take over and over-rule our preferences.

But it was his attempts to connect with us at a human level that cemented universal hate for him. If we had valued his input, his chatty tone might have been delightful. But as he wasn’t even meeting our basic expectations, his tone just made things worse.

Of course more modern examples of failing with delighters exist. Take for example the obsession with custom 404 pages. We tend not to care that many of them are downright unhelpful. So long as they are chatty or gimmicky, then they are good enough for the ‘50 brilliant 404 examples’ article. This overlooks the fact that these pages are trying to recover a negative user experience.

Yes, the human touch will often be multiple times better than the default 404 page. But being unhelpful while cracking jokes, will also provide a rather annoying experience in many contexts. The being helpful bit is more important than that clever reference to a cult TV show you made.

404 pages seem more often designed for Dribbble than they are the person who has come to a dead end while trying to get to the page they wanted.

The circumstances which create this imbalance in experiences are more likely organisational than being down to individuals in my view.

You might have some amazing visual design and copy-writing resource at your disposal. But some projects require more than that. A badly thought out process or system can’t be papered over with delightful visuals and special moments. Until you get this right, your attempt to excite users can fall flat on its face.

If the collective ability of the team lacks a good level of system thinking and design then some experiences will end up being designed quite poorly, despite having great personality.

Your organisation might have an exacting standard of visual design and tone it needs to achieve before anything can ‘get out of the door’. But it might not apply that same high standard to the entire experience. So when a poorly designed experience gets released with a very high level of visual design, it can lead to some tedious experiences for users.

If you want to ‘raise the bar’ of design in your organisation then that bar needs to apply to the full experience and not just some elements of it.

If the design function plays a rather submissive role in the organisation or within the team, it can be difficult to demand a better standard of experience than the thing that is easiest for engineers to produce. But they will be happy to let you polish away at that turd they’ve come up with, once all of the ‘important’ decisions have been made.

You haven’t been allowed to influence much of the experience so you ‘go to town’ with the bit you’re allowed to impact. The result can be a release which fails to meet basic expectations but is peppered with underwhelming delighters.

The thing that gets pitched is the thing the big bosses want to see at the end. Pitching an idea with creative, before you’ve really had time to understand the problem and then design a solution to it, can put you in a difficult position.

The result can be a lovely looking but terrible experience that users resent.

The concept of an MVP is widely misunderstood. This misunderstanding gives people ‘permission’ to release bad experiences.

If you’re polishing up the visual layer and tone of an MVP and releasing it, then it probably wasn’t an MVP in the first place. Instead it was just the crappiest possible version of the thing you wanted to make.

Its crapness wasn’t just in how it looked. It worked badly too. MVPs should be for learning, not shipping.

Much of the causes listed above come down to the level of design maturity within the organisation. It’s easy to make the mistake that your organisation has achieved a high level of design maturity when you see lots of nice looking stuff being shipped and presented.

But unless you’re shipping stuff that works as well as it looks and sounds, then you’re not really that mature at all.

Thanks to Harry Brignull for his help reviewing earlier versions of this post.

AI-driven updates, curated by humans and hand-edited for the Prototypr community