Build Design Systems With Penpot Components

Penpot's new component system for building scalable design systems, emphasizing designer-developer collaboration.

medium bookmark / Raindrop.io |

In many neighborhoods you see the same house built over and over again, like these Chicago Bungalows. They make design and development easier, but are they really what residents want?

As a kid, I didn’t often think about my house. I really loved it when I was growing up, even though there was nothing really all that special or exciting about it. It was just our house. And thought it had no unusual or unique features that made it stand out, it was definitely unique.

Chicago is known for having a particular variant of a house called the Chicago Bungalow. It’s so common that nearly 1/3 of all residences in Chicago are bungalows. My childhood home was different. It was a split-level home in a sea of Chicago Bungalows; one of only a handful in our neighborhood. When we were trying to tell people where we lived (well before the days of GPS) we could direct them to look for the one house on the block that didn’t look like the others.

A long time ago, housing developers realized that they could make a lot more money by mass producing houses. This required that they used standard plans to essentially build the same house over and over. You can go to neighborhoods and see them filled with replicas of the same house. There might be aesthetic differences between the houses (different color, different window styles) but they are all basically the same house. That was the case in the neighborhood I grew up in.

The mass production of houses has some benefit for the homeowner. With cheaper costs, home prices are low. Add in a high supply and it becomes easier for people to be a home owner.

But make no mistake, the true benefit is for the builder. They don’t have to spend money on an architect, the plans are all the same. Builders can buy materials cheap when ordering in bulk. By increasing the supply of houses and churning them out quickly, they can rake in more money.

So yes, both sides benefit, and the basic needs of more homeowners are met. But are the homeowners really getting what they want? Are they happy with the process? This is what is going though my head when I see design systems being implemented.

Design systems have become quite popular in the last few years. They offer a set of reusable components (and patterns) that can be put together in any number of ways to build out an application. They come with standards and guidelines that dictate their use.

Let me state this clearly up front, because I don’t want to cause any confusion: design systems are a benefit to the design process. My current company uses a design system. My previous company was building one when I left. I know first hand how they make a designer’s life easier. I see how they make a developer’s life easier. A well-curated design systems has the potential to be force multiplier for any product team.

Now that the preamble is out of the way, all this comes with one big caution. For all the good that design systems provide, they also have hidden within them a trap that is easy to fall into.

Your team will spend months or even years building out your design system. You build out a large set of components and patterns that your team might need, looking at past projects/applications as a guide. Occasionally, you identify a new component or pattern that needs to be in your product you smartly add them to the product. This eventually slows down as you build a robust design system. All is going as great.

Then a new project starts. You talk to stakeholders. You do some field research with users. Then you dig into the design system to start building a solution. Sounds good right?

But this gets the process backwards. The design system should not be on the leading front of the solution. The goal is to dig into what the user is trying to accomplish and what their needs truly are. Then you can design a solution tailor made to what your users need. The design system should only come into play once the solution is identified.

Design systems can make designers lazy, driving them to think only in terms of the components that are available in the design system.

This is how people fall into a trap when using design systems. They can make designers lazy, driving them to think only in terms of the components that are available in the design system. But design works the opposite way. We should define what the user needs first, then figure out how the design system applies. We get the consistency and broad applicability we need, but don’t lose our core ethos.

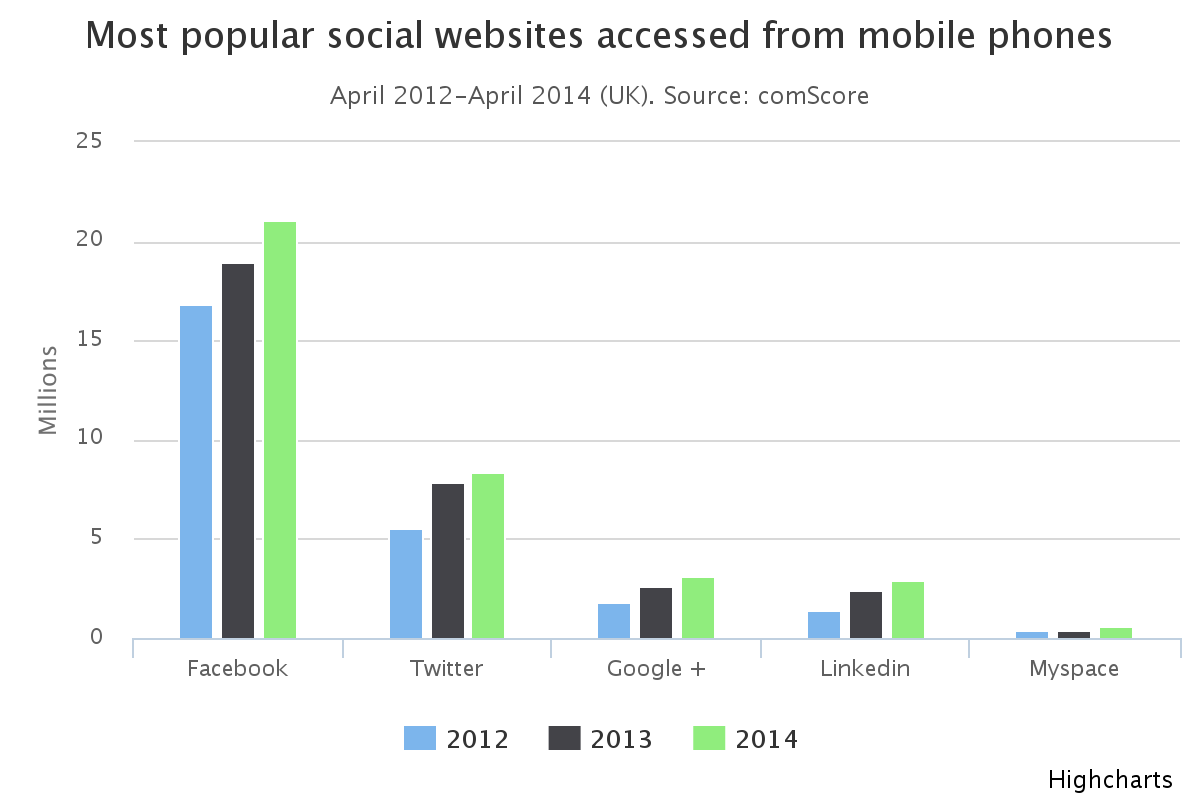

This applies to more than just design systems. This same effect can be seen in many areas of product development. Your company may have access to Tableau or High Charts to serve as libraries of data visualizations. Again, this prevents developers from having to create everything from scratch. But in many cases, the best way for users to extract meaning from the visualization is through a tailored version of a chart. For complex systems, the out-of-the-box solution will only work in a small percentage of cases. Data visualizations will need to be tweaked, modified, and customized to present the information that customers really need.

Highcharts makes building data visualizations like this bar chart easier. But most will need at least a little customization to make them more useful for their intended audience.

Even if you have a customer need that best lends itself to something as simple as a bar chart, there’s a good chance that you should be layering more information on that chart to enhance meaning. While comparing the individual items is important and the focus of the chart, it is often useful to add in referent marks to identify targets that each item is trying to hit. This referent line does not come standard in bar charts and will need to be added by the development team, but you need to consider it and ask for it directly (note: I don’t know if this should be part of the design system or not).

If you are creating a solution that only uses design system components or any other standard library parts, there are two likely reasons: 1) You are designing for a fairly simple problem or 2) You don’t really understand what your users are trying to accomplish. Too often, I fear projects fall under option #2.

I want to be clear that none of this is the fault of design systems or visualization libraries. They are a useful in so many ways. But they are massive investments of time and resources. As such, they inherit a gravity that pulls everything towards them. We need to spend the energy to break free from this and use the design system as intended.

Design first. Design system second.

Our goal is not to mass produce screens. If everything is basically the same, we risk losing our users in the sameness. Our goal is to deliver products that help our users, and that often requires some customization. Design systems can and probably should be part of this, but they should be a massive benefit for our users as much as they are for the product team.

We don’t want a product that is page after page of basically the same thing, just because we already have the components in the design system. Our goals is always first and foremost what the user needs. Everything else flows from there.

AI-driven updates, curated by humans and hand-edited for the Prototypr community